Ibou just received a large chunk of ebony wood from a friend in Cameroon. Ibou, tell me about your wood.

“Its ebony.” How tall is it? “It’s a foot and half.” What shape is it? “I think is a little bit square-rectangle.”

“I really don’t know what to make with that wood. Should I make a nommo, or a kind of thinker, or a masked dancer? Yea, why not? Why can’t I make it a masked dancer… a goofy masked dancer like a hyena? I used to wear a hyena mask. Hooo. Yea, I can make it goofy, because that mask has a big forehead, a bump forehead, and the face is like that…” (mimics chin jutting out.)

“Should I make it a hyena mask? I am still not convinced. When you start chopping that wood, you just have to keep going. I need to get some vague idea. You know, sometimes, when the wood is just all square like this, I think you have to get an idea of what you want to make. When you get a branch or piece of wood with its own shape, it gives you ideas. That is different for me.”

“Should I make it a hyena mask? I am still not convinced. When you start chopping that wood, you just have to keep going. I need to get some vague idea. You know, sometimes, when the wood is just all square like this, I think you have to get an idea of what you want to make. When you get a branch or piece of wood with its own shape, it gives you ideas. That is different for me.”

How do you usually get your ideas? “I don’t know.” How many sculptures have you made? “One, two, three, four, five, six,… hahhaahhaha” Alot, you have made alot… ” Yeah, a lot.” How did you get the ideas to make those? “Hmmm, haahhahahha. All of my sculptures are just like daily life, that’s all. You know what? If I think of something, it is what I didn’t make. I saw some of my sculptures here and I remember, I made something like that. Or some people say…you should make something like that, and I remember yeah, I made something like that. I was just making something out of nothing, out of something, that is how all of my ideas go.”

Do you ever start a sculpture with an idea and find out you don’t like it? “Yeah, it happens. But, still, some other people may like it.. .hahahha.” So you just keep going with it? “I know that I have left a couple of unfinished sculptures that I have known. I don’t like the shape of the wood going there, it will take too much work to fix it so I leave it and start on another wood. Just two that I have known. The one is still home in Bandiagara by the door. It is a Fulani holding his stick like that. The other one, Bah took it and finished it and sold it the next day with some tourists who really liked it. But now I am going to eat my well deserved tiga-diga rice and drink my premier tea, and look at my wood and think… are you going to be a hyena mask or something else?”

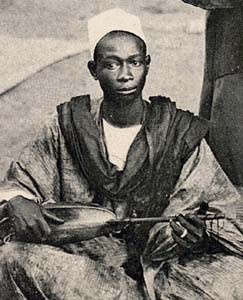

e are the keepers of history and tradition. “Djeli” in Bambara means “blood” because they are the blood of the people. In the past they accompanied kings and nobles as part of their entourage or court, and announced visitors. They provided a summary of their lineage and feats. They also told the stories of the king, nobles and their families. They are very important in a culture where knowledge and history are conveyed orally. Now they are famous top singers and musicians, such as Babani Kone, Kasedi Diabate, Bazoumana Sissoko, Bara Sambarou, Bella Oumar Bella, and Toumani Diabate.

e are the keepers of history and tradition. “Djeli” in Bambara means “blood” because they are the blood of the people. In the past they accompanied kings and nobles as part of their entourage or court, and announced visitors. They provided a summary of their lineage and feats. They also told the stories of the king, nobles and their families. They are very important in a culture where knowledge and history are conveyed orally. Now they are famous top singers and musicians, such as Babani Kone, Kasedi Diabate, Bazoumana Sissoko, Bara Sambarou, Bella Oumar Bella, and Toumani Diabate.

ors, which is shown at left; and house doors, which are larger. Don’t be misled however, if you come across a granary door and wonder how people used such small entries. Granary doors are placed on the square shaped towers Dogons use to store grains. The doors are small to reduce the risk of predators and other invaders from getting in, or easily removing the grain. the largest granaries are for millet, and it is stored with the grain on the seed head. So the door just has to be big enough to reach in and pull out a handful of millet stalks. House doors are larger- usually 70 x 50 cm, but still small by western standards. This is probably due to the scarcity of wood available. Another interesting aspect of these doors are the locks. They come with a wooden key which looks like a stick with some nails sticking through it. They actually work really well. You can see an example of the lock on the door shown above.

ors, which is shown at left; and house doors, which are larger. Don’t be misled however, if you come across a granary door and wonder how people used such small entries. Granary doors are placed on the square shaped towers Dogons use to store grains. The doors are small to reduce the risk of predators and other invaders from getting in, or easily removing the grain. the largest granaries are for millet, and it is stored with the grain on the seed head. So the door just has to be big enough to reach in and pull out a handful of millet stalks. House doors are larger- usually 70 x 50 cm, but still small by western standards. This is probably due to the scarcity of wood available. Another interesting aspect of these doors are the locks. They come with a wooden key which looks like a stick with some nails sticking through it. They actually work really well. You can see an example of the lock on the door shown above.